One of the best ways to separate the strong entrepreneurs from the soon-to-be-frustrated entrepreneurs is to ask them about their goals.

Sharp entrepreneurs set clear goals, which are easy to measure and genuinely contribute to their vision.

Frustrated entrepreneurs talk about their dreams and set micro targets for their days, but these never turn into real progress.

The difference is that good goals feature a number of elements: a clear target, a sense of measurement, a deadline and a reward.

You can test this against your own experiences:

Scenario 1: You and your friends get tipsy and declare “Let’s all get shredded for summer!”

Scenario 2: You set yourself a challenge to lose 8kgs in 4 months, and if successful, you’ll treat yourself to $400 of new clothes.

Which do you think had the higher chance of success?

It sounds obvious when you spell it out, but most entrepreneurs and executives I meet tend to use the first scenario as their template:

“I want us to really do social media well; everyone must post five tweets per week”

“Our goal is to do $1m in turnover next year”

“Let’s aim to subsidise our overheads through a new social enterprise”

“My goal is to really build our Instagram page”

All of these are do-able, but were unlikely to be satisfying.

Each statement hides the real question:

“I want us to really do social media well. Everyone must post five tweets per week”

- What does “well” look like?

- Does “well” mean lots of followers, high quality content, high engagement, engagement from influential people, or just aesthetically pleasing?

- Would it be easiest to buy followers?

- Is forcing your staff to tweet the best way of creating this change?

- What should staff be posting about?

- How will you know it’s working?

“Our goal is to do $1m in turnover next year”

- How much will you get to keep?

- What’s your margin of safety?

- What sort of sales do you want to make?

- Would you prefer higher turnover or higher profit?

- Does the team need to change the projects they accept in order to hit this target?

- Does the team understand how they’re tracking?

- Did you pick $1m just because it sounds cool?

“Let’s aim to subsidise our overheads through a new social enterprise”

- Will this genuinely make your team happy?

- Can you recruit an excellent manager who’s motivated by covering your overhead?

- Will the subsidisation drain cash and prevent the new enterprise from growing?

- Would it be easier to just focus on reducing the overheads?

- Do you actually want two new things; one cash cow and one impact project?

“My goal is to really build our Instagram page”

- What does “build” mean to you?

- Does this translate into sales and margins?

- Is it more important to build a genuine following or to be seen as desirable?

- How will you know it’s working?

- Are your actual customers the same people as your Instagram audience?

- Do you want more engagement or more customers?

In each of these “hypotheticals” the entrepreneur had a good dream, but struggled to pass this on to their team, let alone change their team’s behaviour.

Firstly, their goal didn’t have a well-chosen target.

Secondly, they didn’t have a good metric.

Thirdly, their goal didn’t link to a reward or incentive.

Well-Chosen Targets

Perhaps you’ve heard of a concept called “The Monkey’s Paw” – it’s like a magic lamp that grants wishes, but each wish brings unintended side effects.

You might have seen it The Simpsons Treehouse of Horror II – Homer buys one from a mysterious market.

The wisher asks for something, and while the wish is granted, it does not bring fulfillment.

For example, you ask to become 6’3”, so your forehead becomes 5 inches taller.

Or you ask for $10 million, but everyone else in the world also receives $20 million, making you comparatively poorer.

In The Simpsons episode, Lisa wishes for world peace, but this leads to aliens taking over the planet.

The point of the Monkey’s Paw is that you’re given what you literally asked for, but not granted your underlying desire.

You can buy followers on social media, but when this is exposed you face potential embarrassment.

You can grow your turnover to $1m, but your costs might grow to $1.2m.

You can have a social enterprise that generates cash, but is discredited by customers who perceive it as being “all about the dollars”.

This is a great test of a target – if The Monkey’s Paw gave you literally what you asked for, would it make you happy?

Or is there a deeper need that should be the target?

Perhaps what you really want is financial stability, meaning a constant level of cash in the bank and a higher surplus.

Perhaps what you really want is good content that resonates with your customers, leading to increased sales and an improved reputation within your industry.

Perhaps what you really want is to kill two birds, and are happy to use two stones if that gets the job done.

What Gets Measured Gets Done

We have a natural tendency to improve the numbers that we understand.

Look at Fitbit; as soon as people could visualise their activity (and compare it to the target of 10,000 steps), they started making positive changes to their routines.

Even better, when they got into competitions with friends they ramped up their steps even further.

I once went for a long walk at 11pm on a freezing weeknight to win a challenge, which I never would have considered before.

Similarly, look at the change in behaviour from Instagram hiding likes.

I bet this changes the type of content that gets posted.

Perhaps comments will become the new glamour metric, and posts will be designed to prompt a written reaction.

When we have a way of measuring our performance, we start inventing ways to make those numbers nicer.

This power can be helpful or destructive, so we want to pick a metric that reflects our underlying goal.

Is your step count the right thing to track?

Or should it be how far you can run?

Or should it be your cholesterol readings?

Choosing the wrong metric leads to bad decisions.

Dave Trott explained why we shouldn’t pay for creative work by the hour:

“Counting has taken over from what counts.

And we’ve forgotten the first rule of advertising.

It doesn’t matter what went into it.

What matters is what people get out of it.

Imagine if we judged everything else this way.

Films: ‘No, I don’t want to see that film, it’s only 97 minutes long.

This one is 122 minutes long, that’s a much better film.’

Restaurants: ‘Waiter, can I see a menu with information next to each dish about

how long it took the farmer to grow the vegetables, and what the chef’s hourly rate is?’

Art: ‘I don’t want to go to the Louvre, the Mona Lisa is only 18 inches square.

They’ve got much bigger paintings hanging on the railings outside Hyde Park, let’s go there.’

If we’re looking for a way to judge value for money, we’re using the wrong criteria.”

It’s easy to see this flaw in other people’s industries, but are you making the same mistakes in your business?

Are you measuring the wrong things?

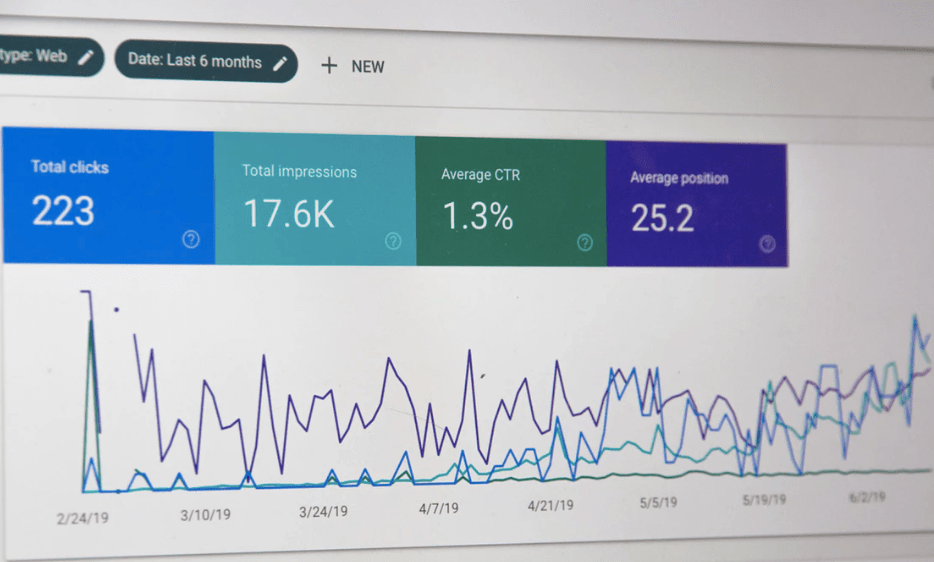

Google Analytics is a great example of metrics without meaning.

Most entrepreneurs have a Google Analytics dashboard, but few know what meaningful insights they can derive from all of those numbers.

What’s considered good?

Are the numbers going up or down?

Why are they going up or down?

Is there a quiet trend that we can’t see day-to-day?

You probably have the ability to deeply understand and track three metrics, which would mean not worrying too much about the other 20-30 indicators.

Maybe it’s page views, maybe it’s acquisition, maybe it’s sales, maybe it’s time on site, maybe it’s geography.

Do you want lots of visitors from around the world?

Or do you want to create a beautiful online experience for your customers in your city?

Both are good targets, but they have completely different strategies and completely different metrics.

The term Clickbait is perfect, you can learn how to trick people into entering your domain, but they’ll quickly work out that you can’t give them what they really want.

Which metrics will you mention to the Monkey’s Paw?

Clever Incentives

Incentives drive most of our behaviour.

Some incentives are “extrinsic”, like a cash bonus for making a certain amount of sales.

Some incentives are “intrinsic”, like cleaning up a beach for the feeling of satisfaction.

Your goal might require unpleasant tasks – what incentive could make these more appealing?

Your goal might be self-rewarding, like how clean eating makes you feel better, or how an active online community becomes a joy to manage – what incentive could get the snowball rolling downhill?

Gimmicks are often useful – if it’s stupid and it works, it isn’t stupid.

The trick is in designing a gimmick that pushes you towards your goal, and which uses a metric that shows your progress.

A Fitbit buzzing at 10,000 steps is a gimmick.

Fun runs are a gimmick.

Sales contests are a gimmick.

Follower counts are a gimmick.

Just keep The Cobra Effect in mind – named after the bounty on snakes in India.

The British government offered cash for dead cobras, but this led to locals breeding more snakes to earn more money.

When this was discovered and discontinued, people let their snakes go free, and the snake infestation was worse than ever before.

Better run your gimmick past the Monkey’s Paw – could your wish lead to a nasty outcome?

Choose The Right Goal And The Teacher Will Appear

Well-named goals are much easier to achieve than broad sweeping statements.

A well named goal gives you a target to aim for, one that genuinely pushes you towards your dream.

A good target lets you see tangible improvements, and helps you identify the ways in which you’re falling short.

By identifying the areas that are short, you can find specialist advisors – especially online – who can teach you how to improve each of these areas.

If your Google Analytics tells you that your images are too large and are slowing down your site, you can learn how to compress them and re-upload them in a few minutes.

That change could see your traffic explode, all because you correctly identified the specific issue and sought out the right advice.

On the other hand, it might not make much of a difference and you need to get advice on content creation.

Both scenarios are useful, because your metrics (watching the change in traffic) guided you to the teacher you needed.

My suggestion is to take your broader dreams and break them into 50 smaller components.

Then give each of them a metric, and run them past The Monkey’s Paw.

Do they still make you happy?

Then pick the top 3 goals and metrics, and seek out the right advisors.

You’ll make rapid progress, and enjoy seeing your numbers improve.

If you’d like to read more on this subject, I recommend the book Atomic Habits by James Clear.

You might also enjoy my article on How To Set Helpful Goals.

For more on The Cobra Effect, you’ll enjoy the Wiki examples of Perverse Incentives.

This post was originally published on IsaacJeffries.com on August 2, 2019. For more insights from Isaac’s work, head over to IsaacJeffries.com and dive deep into his take on social enterprise, acceleration and business models for social impact, and and and… Enjoy!