"From a very early age, we are taught to break apart problems, to fragment the world. This apparently makes complex tasks and subjects more manageable, but we pay a hidden, enormous price. We can no longer see the consequences of our actions; we lose our intrinsic sense of connection to a larger whole. When we then try to “see the big picture,” we try to assemble the fragments in our minds, to list and organize all the pieces. But, as physicist David Bohm says, the task is futile - similar to trying to assemble the fragments of a broken mirror to see a true reflection. Thus, after a while we give up seeing the whole altogether.”

Senge, 1990, p. 3

If I had read The Fifth Discipline by Peter Senge ahead of this season, it’s possible I wouldn’t even have bothered producing it. The oversimplification of complex problems, and our assumption that reverse-engineering a solution is going to help us move forward is at the very core of every conversation I had in season 2.

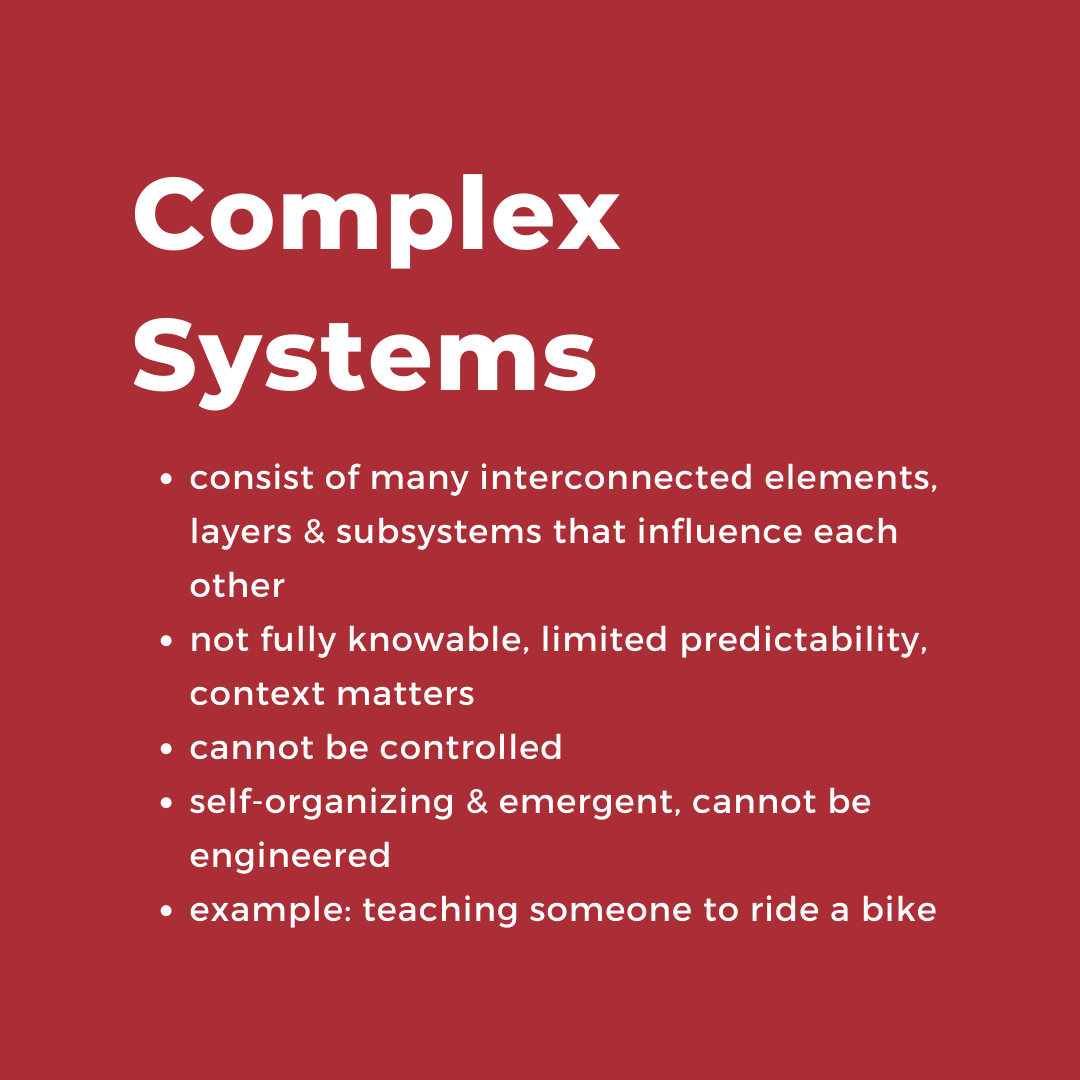

We break down complexity to make it more manageable. We develop solutions based on this simplified view of the world. Then we wonder why we’re barely moving the needle and failing to get to the root of the problem.

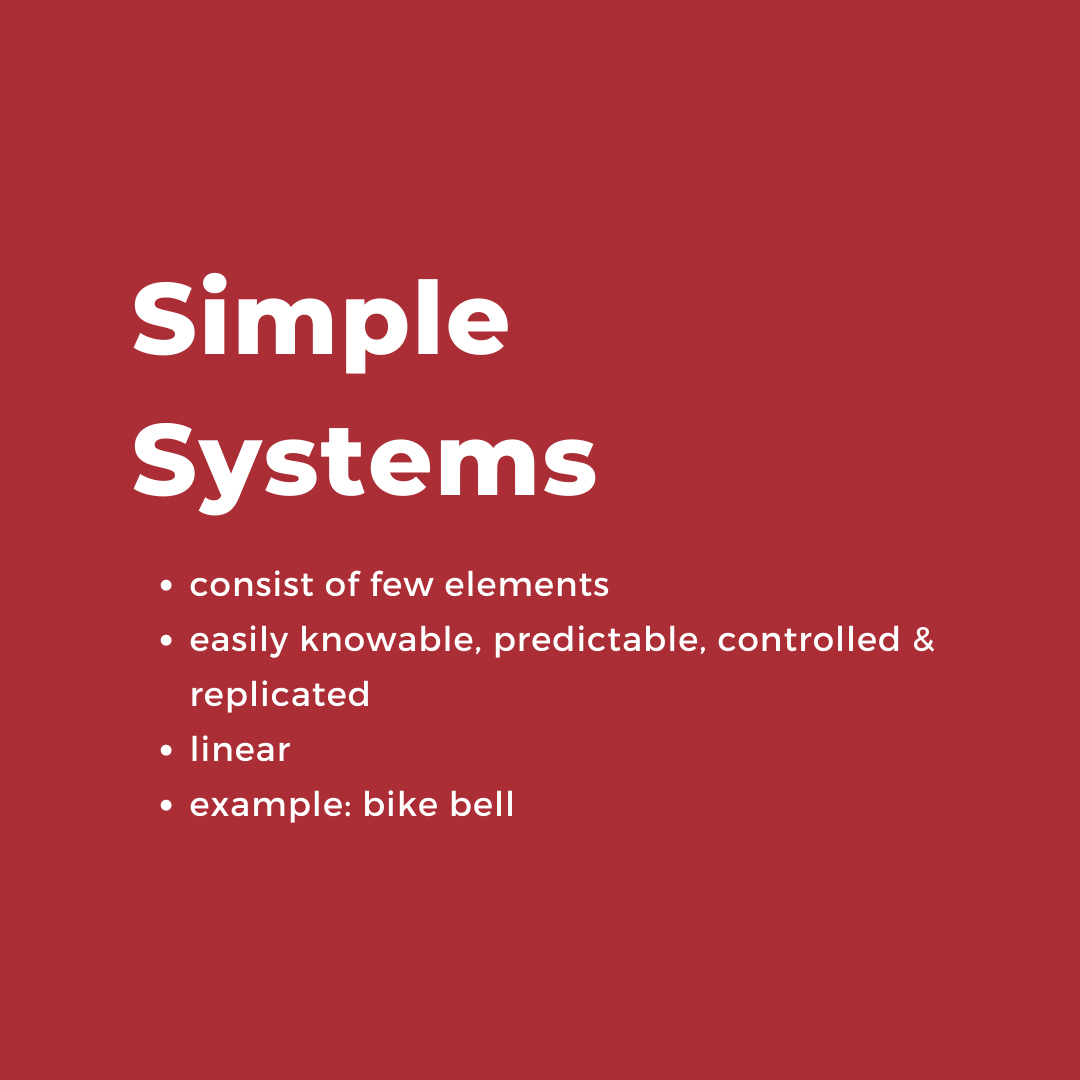

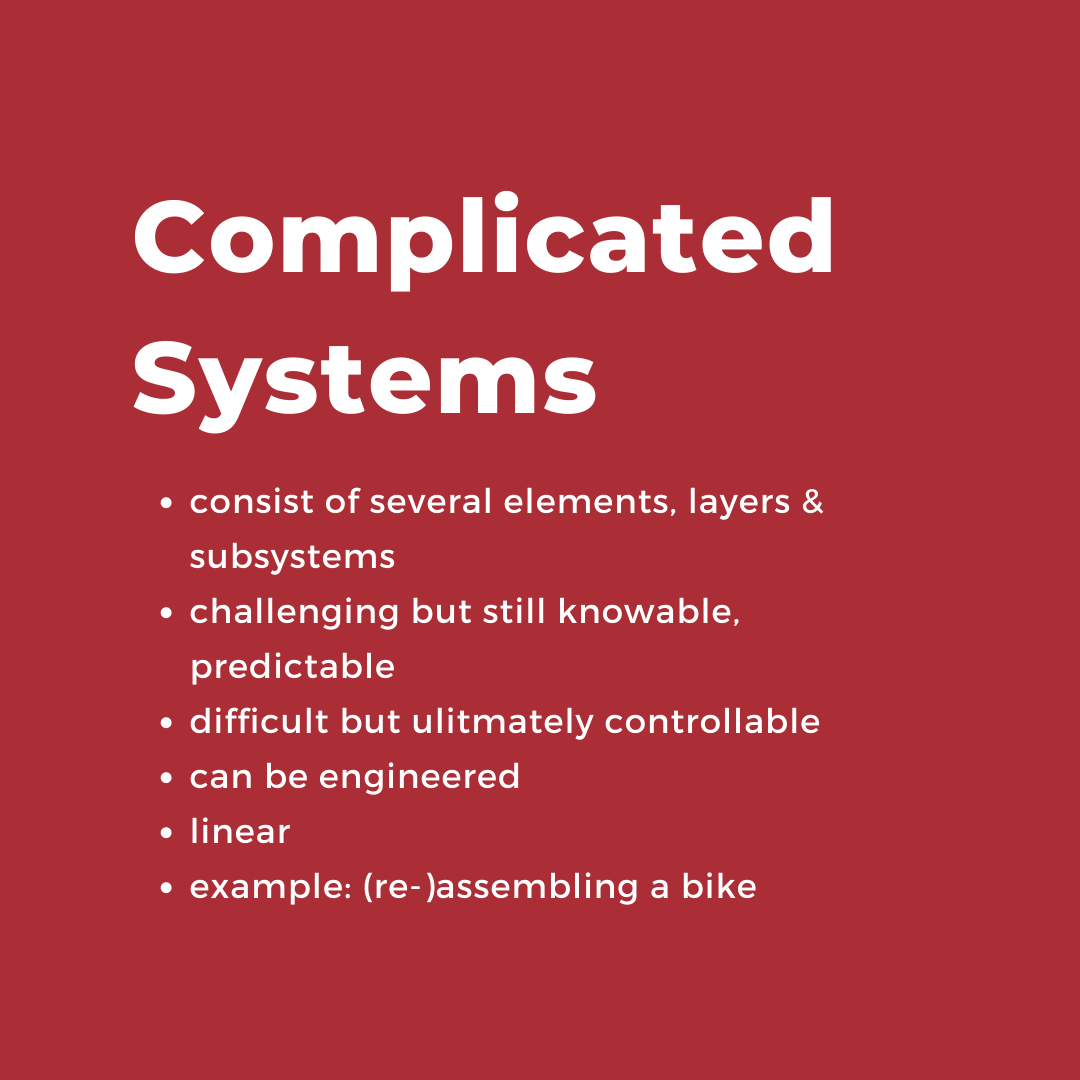

First off: There are times and places when this approach works and makes sense. Namely, simple and complicated problems. If you recall, in episode 1 of this season, we categorized simple, complicated and complex problems. When it comes to building ecosystems for change, we’re talking about complex, adaptive systems. Simplification is not going to cut it.

Secondly, I am convinced that our desire to simplify is natural to us because we’re constantly bombarded with reminders that the world is on fire. Our brains are simply not equipped to grapple with these big, complex issues at all times and still allow us to sleep at night. So we simplify in an effort to make sense of cause and effect, and hopefully we ask ourselves what each of us can do to make a difference. Not because me recycling or bringing my own bags to the grocery store - both of which are acts of rebellion in the US - will put an end to pollution, but because if hundreds, thousands and millions of people joined in this tiny effort, we would actually move the needle. And maybe stand a chance of a good night’s sleep.

This raises the question of leadership in complex, adaptive systems. For too long, we’ve been taught that our so-called leaders - elected officials, CEOs, executive directors and the powers that be - are here to lead us through turbulent times. We call this top-down leadership. There are systems and situations in which top-down leadership is called for (read more here).

Yet, for most of us to become the proverbial change we wish to see in the world, we cannot rely on top-down leadership and systems thinking provides us with instructions bottom-up (eco-) systems change.

In episode 2, Madelynn Martiniere took us on a journey of participatory design and Kate “Sassy” Sassoon showed what participatory democracy and decision making looks like in the form of cooperatives: Both models provide a manual for building the future we want to live in.

I’m hesitant to even use the term system leadership because traditional ideas of leadership distract from what we’re talking about here: the leader as someone who listens, convenes and helps enable others to do their best work and live up to their potential. This has little to do with the traditional notion of leaders that ride ahead into battle in fight for a better world.

Instead Margaret Wheatley helps us re-define a systems leader:

"We give up believing that we design the world into existence and instead take up roles in support of its flourishing. We work with what's available and encourage forms to come forth. We foster tinkering and discovery. We help create connections. We nourish with information. We stay clear about what we want to accomplish. We remember that people self-organize and trust them to do so.”

Wheatley & Keller-Rogers, 1996, p. 38

On a more practical level, here’s what we learned from season 2 about how to support the flourishing of local ecosystems, how we might foster mindsets of tinkering and discovering, how to trust people and systems to self-organize:

Lesson 1: Let go of the illusion of control

We have less control than we think and, once we come to terms with this, you might just see that that’s a good thing! You are NOT responsible for saving the world or even your community. Social change is not about you! Recognize that you’re a small player in the system. Yes, you have an effect on the system. Sometimes unintended and sometimes intentional, sometimes it’s a net positive effect, sometimes it’s negative. And more often than not, it’s hard to tell ahead of time which side the coin will land on. Instead, I suggest we all accept, and find some consolation in the fact that our impact is limited. So let us choose wisely where we want to intervene.

Lesson 2: Rediscover connectivity & relationships

"At any moment, what we see is most influenced by who we have decided to be. Our eyes do not simply pick up information from an outside world and relay it to our brains. Information relayed from the outside through the eye accounts for only 20 percent of what we use to create a perception. At least 80 percent of the information that the brain works with is information already in the brain.

We each create our own worlds by what we choose to notice, creating a world of distinctions that makes sense to us. We then "see" the world through this self we have created. Information from the external world is a minor influence. We connect who we are with selected amounts of new information to enact our particular version of reality.

Because information from the outside plays such a small role in our perceptions, Maturana and Varela note something quite important for our activities with one another. We can never direct a living system. We can only disturb it. As external agents we provide only small impulses of information. We can nudge, titillate, or provoke one another into some new ways of seeing. But we can never give any one an instruction and expect him or her to follow it precisely. We can never assume that anyone else sees the world as we do."

Wheatley & Keller-Rogers, 1996, p. 49

Lauren Higgins described that she learned to think in systems through the metaphor of a tree. Rather than sitting and remaining on one branch, Lauren developed a way of thinking in systems that is more akin to climbing a tree: moving from one branch to the next, considering related topics and questions that allow us to explore a system in depth and more comprehensively.

In my conversation with April Rinne in episode 5, we talked about the superpower of seeing what's invisible. Much like accepting the fact that we have no control, let us accept that most of us are blind to a lot of what’s going on in the world. Not necessarily because we’re ignorant, but because we’ve been taught NOT to see systemic challenges as long as they don’t affect us: Systemic racism and discrimination against minorities, the effects of global warming and pollution, the list is long... In a world that is increasingly complex and whose challenges are on the news around the clock, we have become selective over what we engage with and what we try not to see because it’s A LOT. But that’s no excuse for ecosystem builders. We NEED to rediscover how we’re connected to each other.

Lesson 3: Listen deeply and with curiosity

So, how then do we go about seeing what’s invisible? Sounds a little counter-intuitive, doesn’t it? In episode 3, Lauren Higgins shares some very practical advice with us from systems thinking pioneer Margaret Wheatley:

- Build networks

- Start sharing ideas and talk about what should happen: communities of practice form

- A system of influence will emerge

Another way to truly listen with curiosity is participatory design. As well-meaning changemakers, it’s easy to see a problem, roll up our sleeves and start to solve for it. But our information is incomplete. Even when we attempt to listen, too often we enter these conversation with a hypothesis that we seek to validate. The problem here is that we haven’t been taught how to ask the right questions.

Lesson 4: Slow is better

Learning to see slow, gradual processes requires slowing down our frenetic pace and paying attention to the subtle as well as the dramatic. If you sit and look into a tidepool, initially you won’t see much of anything going on. However, if you watch long enough, after about ten minutes the tidepool will suddenly come to life. The world of beautiful creatures is always there but moving a little too slowly to be seen at first.

Senge, 1990, p. 23

Jeff Bennett and I learned from our experience as ESHIP Champions that we expected too much too fast, and that led to us burning the candle on both ends. Shifting systems and making a difference in the world is not a sprint, friends. It takes time. Culture change, building trust and relationships, changing mental models - all that takes time.

“Particularly when technology is involved, we're used to quick fixes. But just because we can do it fast doesn't mean we should.”

Madelynn Martiniere

Throughout this season I’ve realized that the ONLY way to make a difference is to slow down.

And slowing down is not just the right approach to ensure that you’re asking the right questions, listening with curiosity and co-developing experiments to test solutions. It also keeps you sane! The first of the eight superpowers for thriving in constant change, according to author, futurist and guest April Rinne is to run slower. Not running SLOW. But Slow-er. And she has a good reason for that. April argues that in a world of flux that we find ourselves in, the finish line keeps shifting. The faster we run, the faster it shifts. If, however, we learn how to run slower and enjoy the journey that allows for learning and deep connection, we are more likely to thrive in the choppy waters of constant change.

Lesson 5: Don’t sacrifice yourself

As a dedicated changemaker and ecosystem builder, it’s easy to play the martyr. The work is important, and it’s never done.

At each Startup Champions Network Summit, we make it a priority to set aside one night of the event to talk about the roses and thorns of our work. I like to call it Whiskey and War Stories. And for good reason. There are few safe spaces for us to talk about the hardships of this work. In my conversation with Lauren Higgins I shared how I used to feel responsible for saving the world which - now that I say it out loud - sounds ridiculous of course. But let’s not forget that many of us dedicate ourselves to making a difference in the world because we find the status quo unbearable. And when the problems are nested within complex, adaptive systems, they can feel overwhelming. And no matter how hard and fast we try to run up that mountain, we’re probably not going to solve them in our lifetime but that doesn’t stop us from trying, does it now? This is one of the lessons I personally found most helpful in this season: The reminder that we’re not able to serve our communities long term if we burn ourselves out.

Scratching the surface

Thinking and acting in complex, adaptive systems is a rich topic; we barely scratched the surface in this season. With these fundamentals, may we all become more effective and less exhausted ecosystem builders who can show up for their communities for years and decades to come.

Here are some parameters we didn’t cover but that are absolutely worth exploring more:

- Time lags and feedback loops in complex, adaptive systems

- Leverage points and the small interventions that can have big effects

- Narrative change: Jeff and I touched on it in episode 3 but the importance of narrative in complex adaptive systems would warrant an entire season. Maybe it will one day 😉

Dive deeper: Further reading

- Senge, Peter. The Fifth Discipline. 1990.

- Meadows, Donella. Thinking in Systems. A Primer. 2008.

- Wheatley, Margaret & Keller-Rogers, Myron. A Simpler Way. 1996.

- Brown, Adrienne Maree. Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Shaping Worlds. 2017.

- Feld, Brad & Hathaway, Ian. The Startup Community Way. 2020.

- Sinek, Simon. The Infinite Game. 2018.

Key resources from season 2

- National Center for Economic Gardening

- Dancing with Systems, Donella Meadows

- Community: The Structure of Belonging, Peter Block

- The Art of Gathering: How We Meet and Why It Matters, Priya Parker

- Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds, Arturo Escobar

- The Dawn of System Leadership

- Systems Thinking for Social Change: A Practical Guide to Solving Complex Problems, Avoiding Unintended Consequences, and Achieving Lasting Results, David Peter Stroh

- Flux: 8 Superpowers for Thriving in Constant Change, April Rinne

- The Wisdom of Insecurity: A Message for an Age of Anxiety, Alan Watts

- Mindset: The New Psychology of Success, Carol S. Dweck

- Community Builder: Designing Communities for Change

- Michelle Holliday, The Age of Thrivability

- Crowdcast with Michelle Holliday: THRIVABILITY: A framework for regenerative leadership

- The Culture Map: Breaking Through the Invisible Boundaries of Global Business, Erin Meyer

- For All the People: Uncovering the Hidden History of Cooperation, Cooperative Movements, and Communalism in America, John Curl and Ishmael Reed

- Indigenomics, Carol Anne Hilton

Browse Season 2

Ecosystems For Change: Logbook #2

Welcome to my second logbook, an in-between-seasons update on what’s been going on behind the scenes of this show and in my work in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia.

Read MoreS02E09 – Season 02 Review: Models of Leadership in Systems Change

When we set out on this season, it was all about the great unknown of complex, adaptive systems. Scary, right? After hearing from our seven guests, I hope that things are a little less unknown.

Read MoreS02E08 – Building The Future With An Indigenous Worldview with Vanessa Roanhorse

I’m sitting down with Vanessa Roanhorse to talk about the Indigigenous worldview, how it might inform our approach to thinking in systems, and what exhausts her about being asked to show up as an Indigenous female entrepreneur and educator.

Read MoreS02E07 – Good trouble: Stakeholder Capitalism & Global Cooperativism with Kate “Sassy” Sassoon

I talked with Kate “Sassy” Sassoon about the role of stakeholder capitalism and global cooperativism and how both models help us rethink the current system.

Read MoreS02E06 – Sitting in the Fire: Giving Birth to New Systems with Lana Kristine Jelenjev

Lana Jelenjev, community alchemist, hospice worker for dying systems and midwife for new emerging systems, introduces the two-loop model that explains her work and shares how she sets and upholds boundaries when helping others cross over from old to new.

Read MoreS02E05 – Thriving In a World of Ambiguity, Uncertainty, and Constant Change with April Rinne

I wanted to have a conversation with April Rinne because her book, Flux: 8 Superpowers for Thriving in Constant Change is exactly the kind of thinking that changemakers and systems thinkers need to not only keep their heads above water, but to actually thrive in our constantly changing circumstances.

Read More