The future is rural

Digital economy ecosystems as an opportunity for rural America

When we think of rural America, we may envision cows grazing lazily on the rolling hills of Vermont, spectacular vistas in the mountains of North Carolina and Kentucky, and long fields in Oklahoma that stretch into the horizon, spotted with red-painted barns, tractors and water towers. We imagine lively, quaint downtowns with independently-owned shops and a simpler, slower pace of life.

Few of our thoughts go to the opioid crisis, unemployment, poor health outcomes, and generational poverty that are ravaging our rural communities.

The debate around how we might build more equitable entrepreneurial ecosystems is not a new one. I have written and explored this topic with other ecosystem builders as part of my ecosystem building 101 series. Now that I’ve returned to the field as an active ecosystem builder as Director of Ecosystem Building at the Shenandoah Community Capital Fund, I have the opportunity to put these theoretical considerations into action and see what holds up in practice.

In May 2022, the Center on Rural Innovation (CORI) convened 20+ rural leaders and agents of change from their Rural Innovation Network – a nationwide community of local leaders working to advance the economic future of small-town America. For three days we discussed and explored what opportunities we might leverage to help our communities prosper economically and socially, in particular through the establishment and growth of digital economy ecosystems.

Digital Economy Ecosystems: “How organizations in a community work to align around the common goal of increasing tech employment, and as a byproduct, promote greater economic inclusion in rural communities. An ecosystem involves more open collaboration between many different startups, companies, and entrepreneurs, as opposed to having companies operating in silos.[…] The ecosystem, when functioning properly, creates a cycle of regenerative benefits for investment, training, collaboration, mentorship, and growth.”

CORI, 2022, p. 4

An Unequal Status Quo

In 2021, more than 100,000 Americans died from drug overdoses (CDC 2021), and alcohol abuse causes more than 140,000 deaths each year (2015–2019 average) – the equivalent of more than 380 deaths per day (CDC 2022).

The median American household is poorer in networth today than it was in 2000 while experiencing higher levels of stress, anger and worry.

In 2020, 37.2 million – or 1 in 10 – Americans lived under the poverty line.

According to the 2021 social progress index, the US ranks 24 among 168 nations in terms of (1) meeting their citizens’ basic human needs, (2) foundations of wellbeing and (3) opportunity (Social Progress Index 2021). Some of the tragic highlights include:

- #24 in internet access

- #43 in child mortality

- #53 in premature deaths from non-communicable diseases

- #57 in personal safety

- #73 in maternal death rate

- #97 in equal access to quality healthcare

- #103 in discrimination and violence against minorities

The Urban-Rural Divide

But wait, aren’t these issues across the United States?

True.

And yet, we know that economic shocks such as the Great Recession more harshly impacted rural regions; impacts that are exacerbated the longer they remain unaddressed: Communities like Pikeville, Kentucky, or Danville, Virginia, are dire role models of what happens when anchor industries like manufacturing, tobacco, coal or textiles move abroad or close down for good:

When the economic engine comes to a standstill, rural regions are faced with unemployment, lack of economic opportunity, and poverty – laying the foundation for not only economic but social and cultural decline.

When I spoke to Matt Dunne, founder of the Center of Rural Innovation, in 2020, he explained:

“Springfield, Vermont, was a community that grew based on innovation of its time. It had the highest per capita income in the state of Vermont for forty years based on Machine Tool, a machine tool specialist. Things were going well for a long time: the company attracted labor from all over the world which made its workforce quite international. Then, in the 1970s, Machine Tool started to decline in the US and in Springfield. It continued to slowly recede until it pretty much went away for good in 2000 and the community collapsed. Without a diversified economy Springfield was not able to withstand that kind of withdrawal by a few large multinational companies. It became ground zero for the heroin epidemic in the region.”

The economic base fell out from under it and went on to become one of the highest poverty rates in the state of Vermont.

Matt Dunne, 2020, Social Venturers interview

Unemployment and poverty are only the beginning of long a downward spiral in both macro- and micro-economic terms:

- A decreased tax base reduces spending on public services such as

- Housing and health conditions decline, while

- School drop-out rates, substance abuse and crime skyrocket.

What’s worse, once this spiral is underway, effects begin to self-perpetuate. Slowly but surely, the sense of being reliant on government services and having been left behind seeps into the minds of our communities. Most severely impacted are Black, Indigenous and People of Color who have been subject to systemic discrimination for centuries.

Matt continued: “For the last hundred years, rural and urban places have largely tracked each other in terms of economic performance. Until the great recession of 2008 when all the communities in the US came crashing down. Only the recovery was fundamentally different for urban areas which were quickly climbing well past their pre-recession economic levels.

Recovery for rural communities, however, looked dramatically different. Even as of January of 2020, more than half of the rural counties had not even gotten back to their pre-recession levels. This division was driven by three major forces:

- Automation of traditional rural jobs.

- Globalization both in policy and technology: Supply chains no longer had to be within a drive time but allowed companies low cost labor anywhere in the world.

- The decline of entrepreneurship for the 30 years prior to the recession that took place in rural America.

As a result we had this huge divide between rural and urban America. We could account for most of the difference with digital economy jobs because automation and globalization created a lot of jobs in urban places and took them away almost exclusively from rural places.

Add to it the opioid epidemic in the US (which was a fundamentally rural experience) and the lack of civil society infrastructure: Newspapers went under, television stations went under, and rural communities and smaller micropolitan areas lost their voice in the American civil discourse.”

Digital Economy Ecosystems: An opportunity for rural America

In their 2022 report “How to increase tech talend and tech employment” CORI reports that the digital economy grew 3.5 times faster than the overall economy did between 2005 and 2019 (Bureau of Economic Analysis) accounting for 7.7 million jobs across the U.S. What’s more, for every high-tech job created, an additional three to five jobs are created by local companies. In other words, the economic potential for rural communities to benefit from digital jobs and employment is promising.

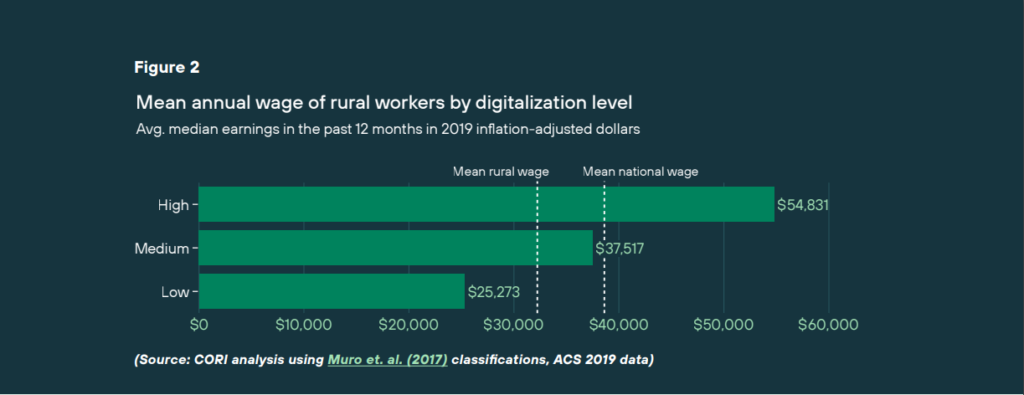

Digital jobs tend to be less location-specific (as long as broadband is available), and the earning potential is exponential: The mean annual wage of rural workers with low digitalization levels lies around $25,000 while those with a high level of digital skills stand to earn more than double ($54,000).

If our goal for the rural communities in which we work is to create more digital employment, we need to be intentional about building digital economy ecosystems.

As ecosystem builders, we prioritize building a sense of trust and collaboration among the different players in the ecosystem (as a foundation for the free flow of information, talent and resources) to create equitable opportunities for all citizens in our communities, minorities in particular.

Colby Hall, executive director at Shaping Our Appalachian Region (SOAR) in Eastern Kentucky shared how a mindset of despair and reliance on government support are passed down from generation to generation in the 54 former Coal-reliant communities, “In too many families, the goal of youth is to become a drawer: Not to practice their artistic skills but to turn 18 so that they can draw social security to help support their families. When the coal mines in Eastern Kentucky shut down and no other industries took their place to economically sustain communities, poverty became a generational issue. The dominant mindset became one of disempowerment and dependence on the government. We’re working to change that by fostering entrepreneurship and rebuilding the regional economy while ensuring citizens are connected through access to broadband.”

CORI’s research found that rural Americans – on the whole – are interested in tech work. The challenge in transforming rural communities to take full advantage of the digital economy is two-fold:

- Convincing rural employers to prepare their companies and employees for a transition toward a more technology-focused approach (in industries where automation and digitalization will increase productivity, efficiency and profitability)

- Preparing rural workers by providing education and training to take these jobs as they come available (as well as qualify them for remote opportunities with companies in urban and metropolitan areas)

The question for local leaders like us then becomes: How might we engage rural communities, and our most vulnerable populations, in a digital economy as either entrepreneurs or employees?

1. Understanding our communities’ needs

Looking beyond demographics, the majority of citizens in our communities hold a multitude of identities (often referred to as intersectionality):

- socio-economic: low-income and/or returning and still incarcerated people,

- race and ethnicity: Latino/hispanic, Indigenous, African-American

- immigration and/or refugee status

- disability

- neuro-divergence

- recovery status from addiction

- LGBTQIA+

- educational status

- levels of mental health and abilities

How do we deepen our understanding of so many lived experiences that aren’t our own?

We become intentional about educating ourselves about the history and experience of the populations in our community. If we’ve never experienced displacement, incarceration or discrimination first-hand, let alone as a permanent bias that inevitably impacts our view and experience of the world, we cannot possibly understand the obstacles and barriers these populations face day-to-day.

2. Understanding other lived experiences

If we’re serious about understanding our community members’ needs, we need to attend events and show up ready to observe, learn and listen. We do our best to leave preconceived notions at the door, we drop our assumptions and show up with an open mindset. That means we are likely entering spaces that we haven’t been in before, that we may need to be invited to, that will most likely make us uncomfortable: be it a church congregation, a community event, a tribal meeting. Let’s remind ourselves that many members in our community experience this type of discomfort all the time. Let’s not assume we’re automatically welcome in these spaces; we must be sure to ask permission and educate ourselves ahead of time about customs in different cultures and contexts. The only way to build lasting relationships and – eventually – trust within our communities is the genuine desire to listen and learn, to remain humble, and to show up consistently.

Be in it for the long-term or don’t be in it at all. Human relationships grow and blossom over time.

In Portsmouth, Ohio, David Kilroy and his team work with community members in recovery from addiction. While often discriminated against, David and his team hired a recovered citizen to ensure whatever they offer meets the needs of the people they’re trying to serve. Once they learned that a “start your own business” workshop would be unsuitable to recovering citizens, they shifted to a model that focused on developing your entrepreneurial mindset which can be deployed in many more situations in daily life than the tall order to become an entrepreneur.

3. Find shared goals and build together

As we gain deeper and more intimate understandings of the lived experiences of the citizens we hope to serve, we open our eyes to the areas in which we and our networks are particularly well suited to engage and support:

- If we have the right connections, we can bring underestimated members of our community to the table and start meaningful conversations.

- If we know who can lend a hand, we can make valuable introductions.

- If we truly and deeply understand what our communities need, we can co-build solutions that address the root cause of issues that plague our rural regions.

Especially as an entrepreneurial support or economic development organization, let us set our organizational goals aside if it turns out they’re not what your community needs right this minute.

In building culturally aware, informed and relevant programming, events and storytelling initiatives, it is key that we base our efforts on the needs and priorities as identified by the community members themselves, not our own agenda. If you can’t meet your community’s needs, then don’t. Step aside and bring other stakeholders to the table who might be more apt at co-creating what’s truly needed. Don’t string your community along for your own organizational goals.

Anita Bringas from UNM Hive in Taos, New Mexico, shared their approach of working with Indigenous communities, “Leaders in tribal communities only serve from January until December of the same year. In such short governance terms, we request a meeting with tribal leadership within the first month of their term to understand their priorities for the year so that we can align our efforts where it makes sense. We don’t ever want to design a program or event that doesn’t support the community in going where they’re already headed.”

4. Decentralize and build community-wide capacity

As ecosystem builders who are interested in their community thriving and evolving into a more prosperous and equitable future, we must ensure that our efforts are sustainable: We have to decentralize the work. Our Executive Director Debbie Irwin likes to remind people:

I am not the ecosystem. I can’t and won’t be the only convener or advocate for what we’re trying to do for underserved communities in the Shenandoah Valley.

Debbie Irwin

As the term ecosystem indicates, no single entity (person or organization) can be responsible for the flow of information, talent and resources within the system. We need to bring others along and decentralize our efforts to ensure they’re owned by all accomplices to ensure sustainability. If our goal is to build thriving digital economy ecosystems that can exist without our constant intervention and support, we are – in a way – trying to work ourselves out of a job. Whatever we build, we must think beyond individuals and individual organizations.

Let the vision be greater than what any one person or organization can achieve on their own and co-build for sustainability.

Creating true equity

We are familiar with our individual life experiences – the way and context within which we were raised, experienced school and community, and go through life. It’s easy to assume that everyone’s experience is the same. In many cases, that might even be true for the people who live in our neighborhoods, work in our offices and hang out in our part of town.

But if we’re truly in the business of building equitable communities, if we want to serve ALL entrepreneurs and job-seekers, we must leave our comfort zones and get as intimately an understanding as possible of THEIR lived experiences.

- Find out what it’s like to try to turn your hair-braiding side hustle into a business that can support your family when you’re a single mother of three in a rural community.

- Get a first-hand insight into what obstacles you’re up against as a tinkerer with a great idea and no support in a town of 22,300 people.

- For a day, walk in the shoes of a rural high school graduate who wants to pursue coding but can’t afford the $35,000 tuition for the college diploma.

- Learn what it’s like to try to get a well-paying job when you’re recovering from addiction, struggle with unstable mental health, are a returning citizen or have different neuro-diverse needs.

If we are genuinely committed to helping our rural communities build opportunities for themselves, we have to look beyond what’s visible at first sight. We can only uncover the deeper systemic issues that created the urban-rural divide in the first place if we dare look under the hood of our communities – as uncomfortable and confronting that might be.